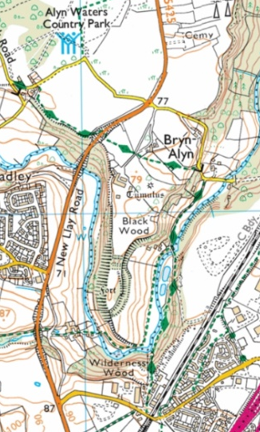

Caer Alyn, or Alyn Fort, is also known as Bryn Alyn (Alyn Hill) camp or fort.

(NGR SJ33125370, NPRN 94754).

Fig 1. Map showing the position of Caer Alyn or Bryn Alyn Fort. Base map © Crown Copyright and database rights 2019 Ordnance Survey.

A scheduled ancient monument, it occupies a promontory that lies on the western side of a piece of land formed by a sharp bend in the River Alyn. On the basis of its banks and ditches, it has been classified as a hillfort dating to the Iron Age (c.800 BC – AD 74 in Wales).

Caer Alyn is not a large fort. Internally, it measures 178m in length by 62m wide, [i] and encloses around 1.25 ha. [ii] However, when its substantial banks and ditches are taken into consideration, it measures approximately 300m in length by 120m at its widest point. [iii]

Many of the earliest hillforts in Wales were small and only lightly defended, surrounded by simple wooden palisades, and sometimes a single bank and ditch. They appeared in the Late Bronze Age or early Iron Age, against the backdrop of population growth and a climate that was becoming cooler and wetter. During this period, land that had previously been suitable for settlement and agriculture could no longer sustain communities and this is believed to have led to greater competition for possession of well-drained and more fertile lowland areas. This must have led to increased conflict between communities and a greater need to claim ownership of land and to define and defend the boundaries of that land.

As the Iron Age progressed, the climate began to improve again and agricultural activity increased. Many hillforts appear to have then been abandoned, while those that remained in use grew in size and complexity, becoming multivallate (having two or more ramparts).

Defences

Despite its small size, Caer Alyn has impressive natural and man-made defences. On the western side of the promontory, the land falls steeply down to the valley bottom. The only remains of any man-made defences here are that of a bank that follows the western ridge, but it is not clear if this dates from the original construction of the fort, or is a section of the early medieval Wat’s Dyke, which is also believed to run along this ridge. A considerable number of large stones litter the western slope, however, and these may be the remains of a stone-filled palisade.

Fig 2. The western slope of the hillfort.

On the eastern and south-eastern sides, the land falls away less steeply, so here the slope was reinforced by a continuous inner rampart and ditch, and an outer rampart and ditch which was also originally continuous; however, the northern half of the outer rampart is now greatly reduced in size and its ditch has silted up.

Fig 3. The top of the eastern rampart, looking out from inside the fort.

Fig 4. The upper rampart and ditch on the eastern side of the fort.

Fig 5. Looking down from the top of the eastern ramparts, to the ditch at its base and the outer rampart.

In 2007, an excavation of a small part of the inner eastern rampart of Caer Alyn was carried out by Tony Hanna, for conservation purposes. The results revealed three phases of construction, starting with a dry-stone wall, possibly the remains of a box rampart (a box-like structure filled with stones or earth), followed by an outer revetment of large sandstones blocks which were placed at the base of the dry-stone wall, perhaps to stabilise it, and ending with a form of glacis rampart, composed of sand and gravels; [iv] this type of rampart was a dump of earth and stones that was positioned immediately behind a ditch, to form a slope that rose continuously from the bottom of the ditch to the top of the bank. The resulting rampart was an imposing and very effective obstacle to attackers.

The glacis rampart appeared in the mid to late Iron Age. This presence of this type of earthwork, along with the fact that Caer Alyn has multivallate defences, strongly suggests that the final form of the banks and ditches date to around the mid to late Iron Age, with older defensive features from an earlier period lying beneath.

At the northern end of the fort, two substantial banks and three ditches cross the 50m-wide neck of the promontory. The inner bank has a level berm or platform along its northern side. There was possibly another bank further inside the fort, but if so, very little of it remains today. The outer ditch is only slight in comparison to the two inner ditches. The ground level within the fort is approximately the same as the ground level outside the fort to the north.

Fig 6. One of the ditches at the northern entrance.

Entrances

Multivallate hillforts, even small ones, often had elaborate and imposing entrances. However, the number of entrances were kept to a minimum, as defensively they were weak points. A small fort such as Caer Alyn would usually only have one. [v]

Research has shown that in southern England, if hillforts have only one entrance, it nearly always faces east, and a second entrance will look towards the west, irrespective of the natural topography. It is believed that these orientations have symbolic significance. [vi] However, no trace of an entranceway over the eastern ramparts has been found at Caer Alyn. Instead, a narrow and steeply inclined depression leading up from the valley to the southern tip of the fort, where the man-made defences on the east and south-eastern side do not quite meet the natural scarp on the western side, is believed to be the original entrance. An opening at this point would have provided access to the river for the inhabitants of the fort, but the approach is steep enough to make it difficult to attack.

Fig 7. Looking up at the southern entrance to the fort. There is little evidence for a gateway here now, but the slight bank on the left of the picture may form part of the original entrance, or possibly be part of the later Wat’s Dyke.

There is another opening into the fort today, across the ramparts in the north-eastern corner. Although the simplest type of entrance into hillforts did consist of just a gap in the ramparts and a causeway across the ditches, [vii] this north-eastern entrance appears to have been formed by simply breaching the top sections of the banks, and only partly filling in the inner ditches. There has been no attempt to make a level surface and the path today contains large pieces of modern brick and concrete. Therefore, it seems most likely that this path is relatively modern, but it is difficult to date as it is not recorded on maps.

It is possible that there was a different type of entrance through the northern ramparts originally. Some hillforts had staggered entrances, so anyone entering would have to thread their way through the ramparts, while observed by guards on the banks. There is little evidence for such an entrance at Caer Alyn today, but it is possible that erosion on the eastern or western sides of the fort has destroyed or obscured the turns of such an entrance.

From at least the late eighteenth century, the fort interior and the land immediately to the north formed part of the Alyn Bank estate, owned by the Trevor family. The land around the southern entrance to the fort was owned and tenanted by different individuals. Perhaps a path was cut across the northern ramparts to allow the Trevors and their tenants direct access to the fort interior.

The Interior

Maps from the late eighteenth century show the interior of the fort and the western ramparts as heavily wooded. By 1843, the northern banks and ditches, described as ‘Little Caer’, were still wooded, as were the eastern and western ramparts, but the interior of the fort was clear of trees and in use as pasture. [viii]

Today, most of the banks and ditches and the interior of the fort are wooded, but there is an open area of grass and brush in the north-west portion of the interior. There have been no surface traces of occupation found there, but a resistivity survey carried out in 2006 in the cleared area produced several features, some of which could be the remains of roundhouses, enclosures or pits. The most interesting feature was rectangular, measuring approximately 5m by 10m, with a possible apse, oriented NE-SW. The ground in the area of this feature also appears to contain a large amount of stone just under the surface. A possible and partial square or rectangular enclosure was also identified. [ix]

In 2008,Dr Meggen Gondek of the University of Chester conducted a gradiometer survey within that part of the fort interior that was clear of trees. Her results corresponded with the resistivity survey in identifying potential structures such as roundhouses, enclosures and pits, including a potential square or rectangular enclosure, oriented NE-SW, with a smaller sub-rectangular or sub-circular structure or enclosure contained within it. [x]

Additional Features

A geophysical (resistivity) survey of the field to the north of the fort, undertaken in 2006, appears to show two substantial ditches orientated EW, with a small break in them, presumably for an entrance. [xi] These ditches may have formed another line of defence for the fort. If so, there may also have been banks with perhaps a timber palisade on top, although there is no evidence for these at present. However, we cannot say whether these ditches pre-date the hillfort, are contemporary with it, or whether they were constructed at a later period, when perhaps the hillfort was reused.

Fig 8. The 2006 geophysics survey of Lodge Field, showing two substantial ditches just to the north of the hillfort.

Aerial photographs of the hillfort show the remains of an oval, banked enclosure at the south-east corner, measuring c.120m NW-SE by 100m. [xii] This feature has not been dated; possible interpretations include an additional defensive feature of the fort or a livestock enclosure. The ground within the enclosure slopes markedly to the north and west.

Immediately to the east of this enclosure, and running on a NS orientation, is a linear feature, while a shorter linear feature runs to the north, on a roughly EW orientation.

Fig 9. Looking up at the fort from the east. The linear feature that runs NS across the field can be seen in the foreground.

In 2008,Dr Meggen Gondek conducted a gradiometer survey within the southern enclosure and identified a number of potential features, including a potential smaller circular enclosure, roundhouses, pits or postholes and ridge and furrow. [xiii] In 2010, resistivity surveys of the same area produced results that may also indicate the presence of round houses. [xiv]

In 2010, we carried out an excavation in this area; one trench, located inside the southern enclosure, failed to produce any significant finds or features, but the second trench, opened on the linear feature that runs on a NS trajectory through the river valley, just below the enclosure, revealed a section of stone revetment with a ditch in front. This feature is clearly visible on Lidar and nineteenth-century maps and has previously been identified only as a field boundary.

Fig 10. LiDAR picture of Caer Alyn hillfort and the southern enclosure. Natural Resources Wales © Natural Resources Wales and database rights.

Function

Hillforts can vary hugely in construction, size, location, and date, and the term ‘fort’ is misleading, as what little excavation has been carried out on them to date shows that they were used for a variety of political, social, military, economic, administrative and ritualistic functions. While some larger forts were in essence embryonic towns, with large-scale, long-term settlements and extensive economic activity, many others contain no obvious evidence of occupation and may have been used only sporadically, as defensive strongholds for short periods of time, for seasonal occupation, communal gatherings, the containment of livestock or the storage and redistribution of locally produced foods and goods.

The Iron Age was a time of huge change, not only in the climate, but in social structures, types and patterns of settlement and technology. The structures and functions of hillforts likewise changed throughout this period, and archaeological features found within them may not have been built or used at the same time.

It seems highly probable that defence was a key motivation for constructing Caer Alyn. Not only does the site appear to have been chosen for its natural defensive features, but it was also considered necessary to add substantial artificial earthworks. Archaeological excavations at other hillforts have provided evidence of conflict during this period, such as burning and stores of sling-stones. It seems unlikely that Caer Alyn could have withstood a prolonged siege, though, as it does not have a natural internal water supply, and access to the River Alyn could have been cut off if attackers had taken control of the river valley.

After centuries of erosion and silting up, the earthworks at Caer Alyn are still imposing but they appear today only as grassy banks and ditches. However, when they were first built, they would have been far more visually imposing, with complex stone and timber revetments and an impressive entrance. As such, the fort would not only have been of practical use for defence, but would also have been highly symbolic, a visual expression of the power, prestige, engineering abilities and access to resources of the community who built it and of the leaders who controlled and directed this community. Caer Alyn would have been an emphatic statement of dominance and ownership of the land, and as such, a focus of tribal identity, as well as a possible place of refuge, for the community that surrounded it.

The visually striking earthworks of forts may also have been a way of advertising an important settlement with specialist functions for the local community. In other hillforts in north-east Wales, such as Moel-y-Gaer (Rhosesmor), Dinorben and Moel Hiraddug, excavations have produced evidence for food processing, weaving, leather- & metal-working. [xv] Although Caer Alyn is smaller than these forts, it may also have been used for the production of some types of specialist goods, or for trade and taxation. Another possible function is the storage and redistribution of agricultural surplus.

In north-east Wales, the cluster of six heavily defended and visually dramatic hillforts which are strategically sited to command gaps in the eastern side of the Vale of Clwyd, such as Pen y Cloddiau or Moel Hiraddug, have tended to dominate the archaeological literature, and the diversity in the structure of forts across the region has meant it has proved hard to discern any regional customs. [xvi] However, the majority of the region’s forts are situated fairly close to the sea or to rivers, [xvii] and also to the divide between the uplands and lowlands. The latter location perhaps struck a necessary balance, allowing access to the more fertile lowlands and also to upland pastures, and also providing forts with a strategic view of the wider landscape. [xviii]

Although Caer Alyn does lie in this upland/lowland zone, it does not provide a good vantage point of the surrounding area. There is a view to the west of the fort, where the land rises to the Welsh foothills, and the ramparts at the neck of the promontory would have provided a clear view north towards Hope Mountain. However, on the southern and eastern sides, the ramparts are at best level with the land across the river (although it should be noted that this landscape has been altered in recent times by mining and clay extraction). It may therefore be that Caer Alyn’s chief strength as a defensive post lay in its ability to observe movement in the river valley below.

If the Alyn was a tribal boundary, Caer Alyn may have been part of a series of smaller forts on the river, along with the Rofft at Marford and Caer Estyn in Hope, that were a first line of defence for a tribal area, and that could send warning of dangertothe forts of the Clwydian range to the west, that provided a second and far stronger line of defence, and guarded the rich and fertile lands of the Vale of Clwyd. However, we do not know whether these forts were all part of the same tribal organisation; although Roman writers recorded that the Deceangli tribe occupied north-east Wales in the late Iron Age, they were only a large regional grouping and the tribal geography may have been much more complex. [xix]

Wat’s Dyke at Caer Alyn

Wat’s Dyke, like the better-known Offa’s Dyke, is a linear earthwork, consisting of a bank of earth and turf, originally fronted by a single ditch on the western side. It is over 62km long and runs along the border between Wales and England, from Basingwerk on the north Wales coast to the confluence of the Rivers Vyrnwy and Morda near Maesbury.

Although Offa’s Dyke is generally agreed to date from the reign of King Offa of Mercia (757-796), there is no secure historical context for Wat’s Dyke and what archaeological dating evidence has been found so far is inconclusive.

However, Wat’s Dyke would appear to be very close in date to Offa’s Dyke.The two dykes bear strong similarities; they are of a comparable size and construction, they run parallel to one another in part of the northern Marches, and they both face west.

The positioning and construction of both earthworks strongly suggests that they were built by Mercia to provide both physical and symbolic barriers to the Welsh kingdoms to the west. The deep ditches on the western sides of the dykes would have effectively limited Welsh movement. Wat’s Dyke especially was carefully placed in the landscape to take advantage of natural west-facing features, so from the banks there would have been clear views into Welsh territory. [xx] The scale and siting of the earthworks also meant that they were imposing visual statements of Mercian power and control to those approaching from the West, which may have deterred potential raiders. [xxi]

While the primary purpose of the dykes appears to have been the definition, monitoring and protection of Mercia’s western frontier, this does not preclude the possibility of cross-border communications. The dykes may have closely controlled movement but also allowed for the movement and regulation of physical goods or cultural exchange between Mercia and Wales. [xxii]

It is generally agreed that both Wat’s Dyke and Offa’s Dyke were too large to be permanently defended along their entire lengths, and no evidence has been found to date for guard posts on the earthworks. [xxiii] However, it has been suggested that there may have been specific points on the dykes that were used to control the passage of people or goods, [xxiv] and Caer Alyn may have been one of these points.

Sections of Wat’s Dyke have been located both to the north and south of the plateau of land on which Caer Alyn is situated. The most direct course between these sections would be along the western edge of the plateau and the fort. Our 2006 resistivity survey in the field to the north of the fort shows a linear feature on the western edge of the plateau which may be the dyke, while at the southern end of the fort, on the western side of the path that today leads up from the valley to what is presumed to be the original entrance, is a slight bank with what may be the remains of ditches on one or both sides; this feature may be part of the original defences of the fort, but equally it may be part of the dyke.

Fig 11. The path leading down from Caer Alyn’s southern entrance, with a bank on the right of the picture that may be part of Wat’s Dyke.

It may be that Wat’s Dyke was positioned on the western edge of the Caer Alyn plateau simply in order to take advantage of the natural west-facingslope which provides views of the Welsh foothills. The River Alyn would also have provided a natural boundary at this point. However, it is possible that the remains of the Iron Age fort and its substantial defences were utilised in some way by the Mercians, possibly as a controlled crossing point. If so, the original earthworks may have been repaired by the Mercians at this time, and there is a possibility that the stone revetment found just below the enclosure at the southern end of the fort, and the ditches found on the geophysics survey to the north, may also date from this period.

The builders of Wat’s Dyke were careful to utilise natural features to increase its defensive capability, and perhaps they used the remains of man-made features in the same way; the Iron Age hillfort at Old Oswestry was also incorporated into the dyke. The remains of the Iron Age hillfort at Caer Alyn may have provided the Mercians with a highly defensible control point over Wat’s Dyke and the River Alyn below.

Endnotes

[i] Retrieved from RCAHMW website (2021). https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/94754/

[ii] Burnham, H., A Guide to Ancient and Historic Wales: Clwyd and Powys, (London; HMSO, 1995), p.61.

[iii] CADW: Welsh Historic Monuments. Ancient Monuments Record Form 1987.

[iv] Hanna, A., Archaeological Conservation and Evaluation at Bryn Alyn Promontory Fort, Caer Alyn Archaeological and Heritage Project, Report No 6, 2008, p.11

[v] Historic England 2018 Hillforts: Introductions to Heritage Assets. Swindon. Historic England, p.7 Retrieved from https://www.historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/iha-hillforts/

[vi] Ibid, p. 7

[vii] Dyer. J., Hillforts of England and Wales, (Princes Risborough; Shire Publications Ltd, 1992), p. 25.

[viii] Flintshire Record Office. NT/M/100 – Trevalyn Estate Sheet 9 (1787). D/BC/4368 – Map of that Part of Trevallyn Estate as lies in the Parish of Gresford – 1799 (amended 1860). Tyler-Jones, V., (Llai Local History Group). Llay: Farms, Houses, Owners and Tenants of 1843-the Tithe Survey (1998).

[ix] Brown, A., Rogers, A., Bunney, A. & Cox, P., 2006. The Bryn Alyn Hillfort (North Section): Geophysical Report (Resistance).

[x] Gondek, M. Report on the Geophysical Survey at Bryn Alyn Fort, Llay, Wrexham. Report for the Caer Alyn Archaeological and Heritage Project on work conducted June 2008 Meggen Gondek, University of Chester Report No.2008/1 July 2008.

[xi] Brown, A. & Rogers, A., 2006. Geophysical Report (Resistance) Caer Alyn Hill Fort, Lodge Field, North of Banks and Ditches.

[xii] Retrieved from RCAHMW website (2021). https://coflein.gov.uk/en/site/94754/

[xiii] Gondek, Report on the Geophysical Survey at Bryn Alyn Fort, Llay.

[xiv] Jones, L., Fraser, T., Roberts, J., Regel, B & Brown, A., 2010. Geophysical Survey (Resistance) Southern Enclosure (Caer Alyn Hill Fort). CHA/BWDS1/2010. Brown, A., Jones, L., Rogers, A., Doughty, A., Elve, E. & Wilson, C. 2010. Geophysical Survey (Resistance) Southern Enclosure (Caer Alyn Hill Fort). CHA/BWDS2/2010.

[xv] Gale. F., ‘The Iron Age’, in The Archaeology of Clwyd, ed. J. Manley, S. Grenter & F.Gale (Clwyd; Clwyd County Council, 1991), p. 89

[xvi] Britnell, W.J and Silvester, R.J. 2018 Hillforts and Defended Enclosures of the Welsh Borderland, Internet Archaeology 48. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.48.7

[xvii] Ibid

[xviii] Manley, J., ‘Small Settlements’ in The Archaeology of Clwyd, ed. J. Manley, S. Grenter & F.Gale (Clwyd; Clwyd County Council, 1991), p. 107.

[xix] Ritchie, M. 2018 A Brief Introduction to Iron Age Settlement in Wales, Internet Archaeology 48. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.48.2

[xx] Hill, D., ‘Offa’s and Wat’s Dykes’, in The Archaeology of Clwyd, ed. J. Manley, S. Grenter & F.Gale (Clwyd; Clwyd County Council, 1991), p.155. Murrieta-Flores, P & Williams, H. (2017) Placing the Pillar of Eliseg: Movement, visibility and memory in the Early Medieval Landscape. Medieval Archaeology, Vol 61, Issue 1, p.94.

[xxi] Worthington Hill, M., ‘Wat’s Dyke: An Archaeological and Historical Enigma’. In Offa’s Dyke Journal, Vol 1, 2019, pp. 77-78.

[xxii] Murrieta-Flores & Williams, ‘Placing the Pillar of Eliseg’. p.99. Worthington, ‘Wat’s Dyke: An Archaeological and Historical Enigma’. p.77. Maund, K., ‘Dark Age’ Wales’ Wales: An Illustrated History, ed. P. Morgan (Gloucestershire; Tempus Publishing Ltd, 2005), p. 74.

[xxiii] Murrieta-Flores & Williams, ‘Placing the Pillar of Eliseg’, p.94. Worthington, ‘Wat’s Dyke: An Archaeological and Historical Enigma’. p.77

[xxiv] Murrieta-Flores, P & Williams, H. (2017) Placing the Pillar of Eliseg’, pp.99-100